下一个: 节流阀,长孔口 上一级: 流体截面类型:气体 上一页: 气管(Fanno) 目录

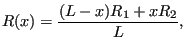

本节考虑具有可变横截面和摩擦的旋转气管。虽然Fanno气管是旋转气管的特殊情况,但其控制方程构成了本文所给方程的奇异极限。因此,对于无旋转且横截面恒定的气管,此处的方程不适用。方程 (87) 的等价形式现在为([32],第515页表10.2):

其中 ![]() 是旋转轴的最短距离,

是旋转轴的最短距离,![]() 是

旋转速度,

是

旋转速度,![]() 是管道的局部横截面。假设管道半径

是管道的局部横截面。假设管道半径 ![]() 沿其长度

沿其长度

![]() 线性变化:

线性变化:

|

KK|(112) |

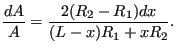

对于 ![]() ,可得:

,可得:

|

MJ|(113) |

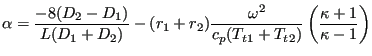

对于 ![]() 、

、![]() 、

、![]() 和

和 ![]() 取管道端部值的平均值,可得方程 (111) 中第二项为

取管道端部值的平均值,可得方程 (111) 中第二项为

![]() ,其中:

,其中:

|

QK|(114) |

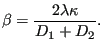

和:

|

SN|(115) |

因此,方程 (111) 现在可以写为:

![$\displaystyle \frac{dZ}{Z} = \left [ \frac{1+\frac{\kappa-1}{2}Z }{1-Z} \right ] (\alpha + \beta Z) dx,$](img580.png) |

RB|(116) |

或(使用部分分式):

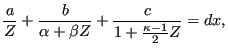

|

WY|(117) |

其中:

|

JR|(118) |

![$\displaystyle b= \frac{2(\alpha+\beta) \beta }{\alpha[\alpha(\kappa-1)-2 \beta]}$](img583.png) |

RY|(119) |

和:

![$\displaystyle c=\frac{-(1+\kappa)(1-\kappa)}{2[\alpha(1-\kappa)+2 \beta]} .$](img584.png) |

KY|(120) |

从上述方程可以看出,对于无旋转且横截面恒定的管道,![]() ,

,![]() 和

和 ![]() 变为不确定值。因此,虽然Fanno气管是特殊情况,但本公式不能用于此单元类型。积分方程 (117) 得:

变为不确定值。因此,虽然Fanno气管是特殊情况,但本公式不能用于此单元类型。积分方程 (117) 得:

其导数为:

![$\displaystyle \frac{\partial f}{\partial M_1} = - \left [ \frac{a}{Z_1} + \frac...

KS|...ta Z_1)} + \frac{c}{\left ( 1 + \frac{\kappa -1}{2} Z_1 \right) } \right] 2 M_1$](img587.png) |

JT|(122) |

和:

![$\displaystyle \frac{\partial f}{\partial M_2} = \left [ \frac{a}{Z_2} + \frac{b...

YZ|...a Z_2)} + \frac{c}{\left ( 1 + \frac{\kappa -1}{2} Z_2 \right) } \right] 2 M_2.$](img588.png) |

PH|(123) |

专注于亚音速范围,有

![]() 。因此,方程 (121) 中唯一可能产生问题的是第二项。这是因为

。因此,方程 (121) 中唯一可能产生问题的是第二项。这是因为 ![]() 和

和 ![]() 不一定具有相同的符号,因此对数可能未定义,即函数

不一定具有相同的符号,因此对数可能未定义,即函数

![]() 在管道两端之间可能有一个零点。这归结为条件(参见方程 (111)),即在单元的一部分中马赫数增加,在另一部分中减小。

在管道两端之间可能有一个零点。这归结为条件(参见方程 (111)),即在单元的一部分中马赫数增加,在另一部分中减小。

一般来说,管道收敛和摩擦导致马赫数增加,发散和离心力导致马赫数减小。计算过程中应避免声速条件。特别是如果收敛计算结束时观察到声速条件,结果可能不正确。

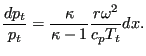

虽然旋转管道是绝热的,即没有热量传递到环境,但由于旋转能量转化为热量或反之,总温度会发生变化。离心运动导致总温度增加,向心运动导致总温度减小。总温度的变化量为 [32]:

|

JK|(124) |

对于线性变化的半径,积分得:

![$\displaystyle T_t - {T_t}_1 = \frac{\omega^2 }{c_p} \left [ r_1 + \left ( \frac{r_2-r_1}{2} \right ) \frac{x}{L} \right ] x.$](img593.png) |

XH|(125) |

对于 ![]() 评估此表达式得到管道两端的总温度增加。为了估计总压力增加(例如获得合理的初始条件),可以再次使用 [32] 中的公式(忽略摩擦效应):

评估此表达式得到管道两端的总温度增加。为了估计总压力增加(例如获得合理的初始条件),可以再次使用 [32] 中的公式(忽略摩擦效应):

|

BV|(126) |

代入 ![]() 的线性关系和刚刚推导的

的线性关系和刚刚推导的 ![]() 结果,得:

结果,得:

![$\displaystyle = \left( \frac{\kappa }{\kappa-1}\right) \frac{\omega^2}{c_p} \fr...

MY|...ft [ r_1 + \left( \frac{r_2-r_1}{2} \right ) \frac{x}{L} \right ] x \right \} }$](img597.png) |

SZ|(127) | |

| NT| | ![$\displaystyle = \left ( \frac{ \kappa }{\kappa-1}\right) \frac{2\left [ x + \fr...

ZS|...2 + \frac{2Lr_1}{r_2-r_1}x + \frac{2Lc_p {T_t}_1}{\omega^2(r_2-r_1)} \right ] }$](img598.png) |

ZZ|(128) |

| NT| | ![$\displaystyle = \left ( \frac{ \kappa }{\kappa-1}\right) d \ln \left [ x^2 + \frac{2Lr_1}{r_2-r_1}x + \frac{2Lc_p {T_t}_1}{\omega^2(r_2-r_1)} \right ].$](img599.png) |

VY|(129) |

最终积分得:

![$\displaystyle \frac{{p_t}_2}{{p_t}_1} = \left [ 1 + \frac{L \omega^2}{c_p {T_t}...

TK|...rac{r_1+r_2}{2} \right ) \right ] ^ {\left (\frac{\kappa }{\kappa-1} \right)} .$](img600.png) |

RP|(130) |

需要注意的是,旋转气管应在相对(旋转)系统中使用(因为离心力仅存在于旋转系统中)。如果在绝对系统中使用,必须在前放置一个绝对转相对单元,并在其后放置一个相对转绝对单元。

旋转气管由以下参数描述(按 *FLUID SECTION 下面的行中的顺序指定,TYPE=ROTATING GAS PIPE 卡片):

示例文件:rotpipe1 到 rotpipe7。